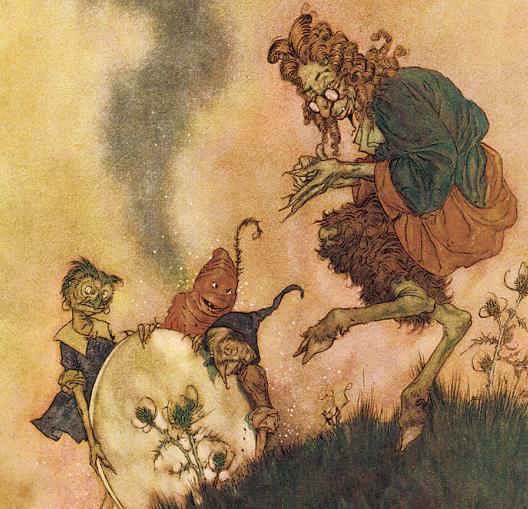

Perhaps the only sensible answer to this question is what do you mean by fairies? After all, if you define fairies as little humanoids the size of butterflies, with gossamer wings, who help hedgehogs and children and never lose their temper, the answer will be no, fairies do not exist.

If you define fairies as a series of phenomema experienced by certain individuals, then even the most hardened sceptic must answer ‘yes’. After all, some individuals clearly have unaccountable experiences that need to be explained even if we decide they are happening in, not outside their heads.

But do fairies exist outside our heads or are they just a product of abnormal or ‘special’ brains? The fact that fairies are typically seen by children, at night, alone or while the witness is in bed should all set off warning clankingly loud bells. But as the sceptic has an easy time of it let’s, instead, concentrate on four reasons for taking fairy sightings seriously as an external reality.

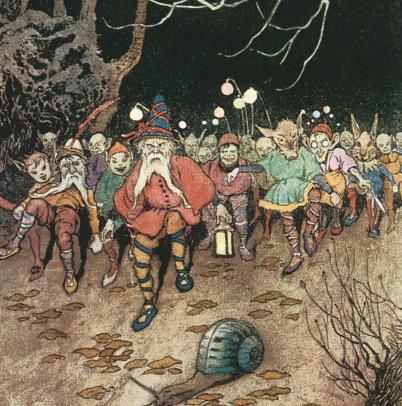

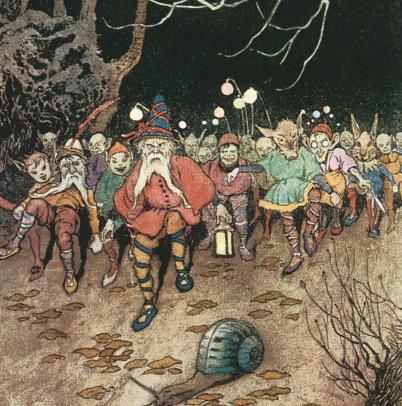

First, the great number of fairy sightings. It is true that fewer people see fairies today than did in the past. But even in the materialistically-inclined, urban twenty-first century the number of sightings of supernatural but living humanoids (our definition of fairies) is surprisingly high. It is not just a question then of explaining away three or four ‘weirdos’.

Second, the type of witnesses. Many witnesses are men and women who might be said to be psychically-inclined: that is to say that, whether psychic phenomenon exist or not, these individuals believe that they are privy to special insights and even visions. It would not be particularly suprising were a medium, say, or a psychic to see a fairy. But, on other occasions, we have sightings from individuals who declared themselves to be sceptics but whose minds have been changed by something that they cannot account for.

Third, the consistency of fairy sightings. Themes repeat themselves in fairy sightings. Fairies often do the same things when seen by witnesses, even witnesses who don’t apparently know much about fairy lore. For example, fairies again and again, are seen dancing in circles, even when those who see the fairies knew nothing (or claim to know nothing) about dancing fairies. Of course, it could be that they fairies dance because of some psychological stimuli buried deep within us and this psychological stimuli works in the same way in different individuals. If so neither sceptics nor believers have come, though, close to explaining the fairy dancing stimulus.

Fourth, fairies like particular places It is not clear why but fairies tend to appear in the same location, in the same way that ghosts are often associated with the same room or the same corridor. Why does this suggest the authenticity of fairy sightings? Quite simply because some individuals who see fairies are not aware that fairies were associated with the place where they had their fairy experience.

No self-respecting sceptic will have had their ‘faith’ shaken too much by this little list. For one, there is simply not the raw data to lead to any conclusions. However, let’s just keep the door open to belief. If fairies do exist how can we possibly explain them?

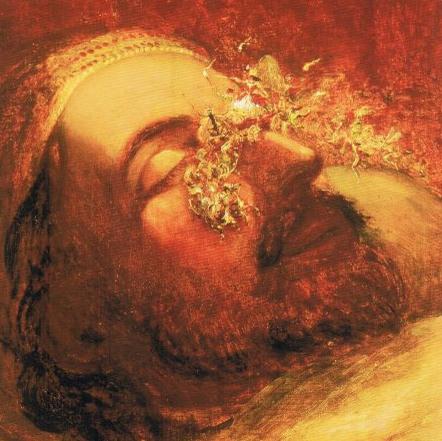

There have been various attempts to do so over the years. However, there is no question that the most popular modern explanation is that fairies are nature spirits. That is to say that when we see fairies we are actually seeing spirits of natural processes be that a tree growing, a fire burning, a rock being…David Boyle, for example, suggests that fairies might be ‘some hidden aspect of natural processes, the personification of rotting or photo-synthesis’, say. It has to be said that fairy lore includes very little of this: here we have a late nineteenth-century reinterpretation of fairy lore at the hands of theosophists. Of course, that does not mean that is it not true.

Another approach that tries to break the gap between belief and disbelief claims that fairies are personifications of natural and other processes that, through human passions, take on an actual external reality and become independent of the mental processes that created them. There is no question that belief though in any external reality for fairies is anti-scientific, at least anti the science we have now at hand. Whether that is a good thing or not is another question.