The primary legend of the leprechaun (aka leithbrágan, leprechaun, lepreehawn, leprehaun, lioprachán, luacharman, lubrican, lugharcán, lugracán and lupracán) is quickly told: ‘The best known of [the Irish solitary fairies] is the Leprecaun… He is seen sitting under a hedge mending a shoe, and one who catches him and keeps his eyes on him can make him deliver up his crocks of gold, for he is a rich miser; but if he takes his eyes off him, the creature vanished like smoke (Yeats, Writings 22).’ With this attractive legend tucked under his arm – and a slightly earlier story about a purse with one auto-renewing shilling – the Leprechaun has slowly shuffled his way to the front of the long queue of Irish fairies. He is perhaps better suited to modern fairy tastes as he rarely hurts anyone, though he frequently makes fools of those who capture him. In modern tales, as Yeats notes, he is invariably a solitary fairy, which is somewhat strange as he spends his time drinking and smoking (quintessentially social activities) and making shoes for others: for the fairies by some accounts. But there are hints in early Irish writing that this might not always have been so disinterested in the company of others. An early medieval text describes how King Fergus was taken by a group of lucorpans to the sea: were leprechauns once mermaids?! Fergus awakes and grabs three of his captors, sparing their lives in return for a wish. The philology that leads us from lucorpan to leprechaun is long and painful Fergus’ demand for a wish and modern Irish men and Irish women demanding money shows a thread of continuity over twelve or thirteen hundred years. Not many fairies can boast that…

The primary legend of the leprechaun (aka leithbrágan, leprechaun, lepreehawn, leprehaun, lioprachán, luacharman, lubrican, lugharcán, lugracán and lupracán) is quickly told: ‘The best known of [the Irish solitary fairies] is the Leprecaun… He is seen sitting under a hedge mending a shoe, and one who catches him and keeps his eyes on him can make him deliver up his crocks of gold, for he is a rich miser; but if he takes his eyes off him, the creature vanished like smoke (Yeats, Writings 22).’ With this attractive legend tucked under his arm – and a slightly earlier story about a purse with one auto-renewing shilling – the Leprechaun has slowly shuffled his way to the front of the long queue of Irish fairies. He is perhaps better suited to modern fairy tastes as he rarely hurts anyone, though he frequently makes fools of those who capture him. In modern tales, as Yeats notes, he is invariably a solitary fairy, which is somewhat strange as he spends his time drinking and smoking (quintessentially social activities) and making shoes for others: for the fairies by some accounts. But there are hints in early Irish writing that this might not always have been so disinterested in the company of others. An early medieval text describes how King Fergus was taken by a group of lucorpans to the sea: were leprechauns once mermaids?! Fergus awakes and grabs three of his captors, sparing their lives in return for a wish. The philology that leads us from lucorpan to leprechaun is long and painful Fergus’ demand for a wish and modern Irish men and Irish women demanding money shows a thread of continuity over twelve or thirteen hundred years. Not many fairies can boast that…

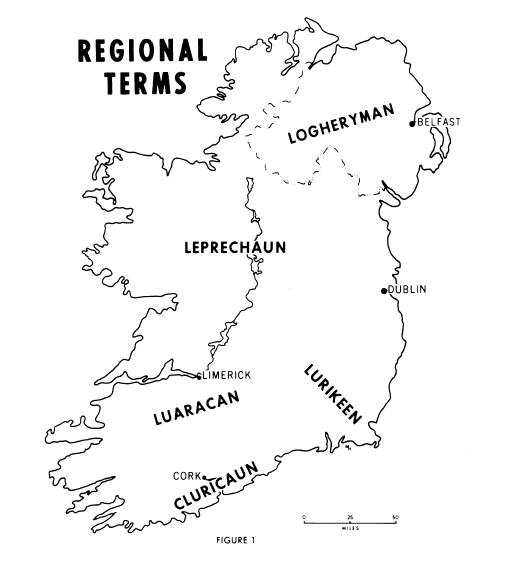

Home region: The word Leprechaun was found above all in the Irish Midlands and Connaught. In other parts of Ireland the Leprechaun goes by different names: the Logheryman in Ulster, the Lurikeen in Leinster, the Luaracan and the Cluricaun in Muster. There is a consensus among fairyists that these are all different spellings and forms of the same word. However, this seems linguistically unlikely and the leprechaun has effectively colonized neighbouring fairies.

This map from Winberry 65

Physical Description: There is a general consensus that the leprechaun is small: not something generally true of other Irish fairies. He seems to be a foot and two feet hight. The leprechaun dresses sharply. McAnally, for example, tells us that he has a red coat with seven rows of buttons and seven buttons on each row with a cocked hat, ‘on which he sometimes spins’! Consider instead now this medieval description: he has a ‘gold embroidered tunic’, ‘a scarlet coat’ with ‘hair that was ringletted… of a fair and yellow hute… and skin whiter than foam of wave and… cheeks redder than the forest’s scarlet berry.’

Earliest Attestation and Etymology: A being called a lucorpan is mentioned in an early medieval Irish poem. A later medieval account refers, instead, to lupracans. There is agreement – including an authoritative statement by the great Irish Celticist Daniel Binchy – that these are the ancestors of our leprechaun. Modern writers have tried to explain leprechaun as ‘Leith bhrogan’ or ‘one shoe maker’. However, this has nothing to do with the ancient form and smacks of popular etymogy. The original form may have been luch-armunn small warrior or, according to Stokes’ plausible suggestion, lu-corp (small-body). The first element is more certain than the second. The first English reference recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary comes in 1604 in the second part of the Honest Whore by Middleton (iii. i) ‘As for your Irish lubrican, that spirit Whom by preposterous charms thy lust hath rais’d In a wrong circle.’

Leprechaun Locations: Leprechauns are commonly found in lonely places tapping away at their shoes.

Leprechaun Sighting: Chasing Leprechauns; Liverpool leprechaun scare; a Leprechaun sighting; Leprechaun in Clare; and the Leprechaun’s Shoe.

Leprechaun Story: Clever Tom and the Leprechaun; The Leprechaun in the Garden; the Three Leprechauns; Leprechaun in Court.

Associated sayings: ‘Tell me where the gold is or I’ll cut you to ribbons!’

Popular Culture: The leprechaun became part of Hiberno-American culture after the Second World War. Its appearance in St Patrick Day’s celebrations and in fancy dress shops was perhaps to be expected: likewise its place in children’s games is predictable enough given its penchant for hiding money or presents. However, in the early 1990s leprechauns took on an entirely new and unexpected direction when they became stars of various American horror films. The first appeared in 1993 and was memorable for a first terrified performance from Jennifer Aniston and with the winning byline ‘Your luck just ran out’. Anyone can make a bad film but the fact that there was a series of six and that other films have also demonized the leprechaun suggests that this might be a permanent shift in the leprechaun myth. Bearing this tendency towards terror, it is nice question whether the Liverpool sightings of leprechauns, which were not particularly pacific, involved the first hint of this desire to portray leprechaun violence.