I have been looking into a very odd book, and I am going to tell the story of the Asiki, or Little Beings, first observing that the singular is Isiki. Well, it is said that the Asiki were once ordinary, human children, but were caught, when young and defenceless, by wizards or witches, and were dragged into the black depths of the forest, where there was no help for them, where no one could hear their cries. The wizards cut off their tongues as a first measure; and so they never speak again, and cannot inform against the magicians. They are then carried away, and hidden in a secret place, where they are subjected to magical processes which change their whole nature, so that they are no longer mortal. They forget their homes, their fathers and mothers and all their kinsfolk. Even the hair of their heads changes. Instead of being crisp wool, it becomes long and straight and hangs down their backs. At the back of their heads they wear a curious comb-shaped ornament, made of some twisted fibre. This they value almost as part of their life, just as in another quarter of the world there are people who drive motorcars and cherish little images and idols and grotesque figures, which are believed to constitute a most powerful protection. These Asiki will sometimes be seen walking on dark nights, and are occasionally met on their walks. It is believed that if a person is either naturally fearless, or made fearless by charms and spells, and dares to seize an Isiki and snatch away the comb, the possession of this mascot will bring him great wealth. But he will not be allowed to remain in peaceful possession of it. The Isiki, in a state of misery and desolation, will be seen wandering about the place where the magic comb was taken from it, endeavouring to get it back. And as late as the year 1901 strange things were told of these Little People in Libreville, French Congo. A certain Frenchman, known to be a Freemason, returning from his restaurant dinner to his house one evening noticed a small figure keeping pace with him on the other side of the road. He called out, ‘Who are you?’ There was no reply; the figure kept on walking, advancing and retreating before him.

A few nights later, a negro clerk in some trading house met the Isiki near the place where the Frenchman had encountered it. And the Little Being began to chase the negro. He ran for his life, and told his master, the trader, what had happened. He got laughed at for his pains, and the next night the trader told the tale to a select company of white men and black women, the Freemason being present. And he said, ‘Your clerk did not lie; he told the truth. I have myself met that Little Being, but I did not try to catch it.’ Then the black women spoke of the odd comb-ornament, and of how the Asiki treasured it, and of the good fortune it would bring to anybody who could capture it. Whereupon the Frenchman – otherwise the Freemason – said, ‘As the Little Being is so small, the very next time I see it I will try to catch it and bring it here, so that you can see it and know that this story is actually true.’

Soon after, the Frenchman and the trader went out at night and tried to find the Isiki. No Little Being was to be found, but a few nights later the Frenchman met it near the place where it had been seen before. He ran forward and tried to catch it, but the Isiki eluded him. However, he succeeded in snatching the comb, and ran with it towards his house. The Little Being was displeased and ran after him to recover the charm. Having no tongue, it could not speak, but holding out one hand pleadingly and with the other motioning to the back of its head, it made pathetic sounds in its throat, thus pleading that its treasure should be given back to it. It followed the Frenchman till the lights of his house began to shine, and then it disappeared. The Frenchman showed the comb to his friends, both black and white, and all agreed that they had never seen anything like it before. From that night the Isiki was often seen by negroes, who were afraid to pass that way in the dark. It followed the Frenchman persistently, pleading with its hands in dumb show, and making a grunting noise in its throat. The Frenchman got tired of all this, and made up his mind that he would give the comb back. And so next night he took it with him; and also a pair of scissors. The Little Being appeared and followed him. He held out his hand, with the comb in it. The Isiki leapt forward and snatched at the talisman and secured it, and the Frenchman tried to catch the Isiki. The Little Being was too agile, however, and escaped; but the Frenchman snipped off a lock of the long straight hair with his scissors, and brought it home and showed it to his friends.

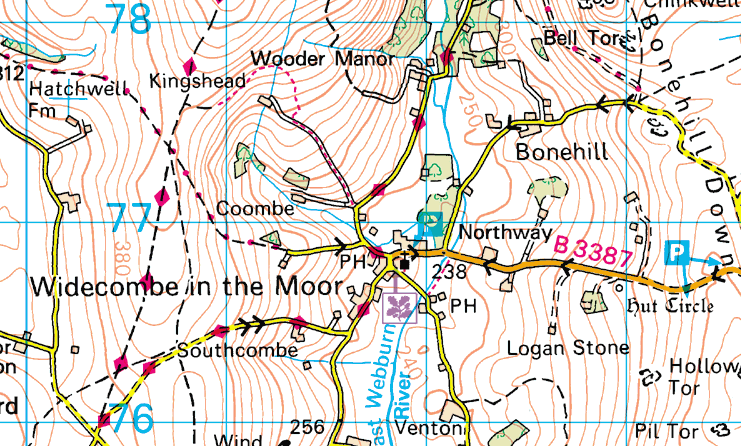

Such is the story told by Dr. Robert H. Nassau, an American missionary, who had worked for forty years in Africa. He seems to fear that his tale will be regarded as incredible. It seems to me, on the contrary, highly, probable. Naturally, one dismisses that part of it which relates to the process by which these Little Beings are made, and that part of it which ascribes to them immortality. The Little People were not made out of little woolly piccaninnies by the magic arts of the wizards; and probably, if one could be caught and examined, it would be found that it had a tongue in its mouth, like any other human being. The fact is that here, in all likelihood, we have a pretty exact parallel to the Little People of our own folk-lore: the Daione Sidhe of Ireland, the Tylwyth Teg of Wales. The substratum in both cases is the same: an aboriginal people of small stature overcome and sent into the dark by invaders. In Britain and Ireland the dark meant subterranean dwellings made under the hills in the wildest and most remote parts of the country; they will point you out the place of these dwellings in Antrim to this day, and tell you that they are Fairy Raths. And in nine cases out of ten you may accept the statement with entire confidence; so long as you define ‘fairies’ or ‘the People’ as small, dark aborigines who hid from the invading Celt somewhere about 1500–1000 B.C. And in Africa the dark meant the blackness of the forest; places hidden in the thickest tangle of trees and undergrowth, protected, perhaps, from all outsiders, black or white, by a maze of narrow paths winding in and out of a foul swamp. And as to the legend of the torn-out tongues, of the guttural noises made by the Asiki; is it not the case that the Little People of the genuine Celtic tradition are also silent? I will not be sure; but I incline to think that this is so. They beckon, they gesticulate, they are seen by Irish countrymen playing at hurly: but they say nothing – the reason being that they do not speak the language of their conquerors. I have seen a monoglot Englishman in Touraine behaving much as the Isiki behaved to the Frenchman at Libreville, even to the making of unearthly sounds and the indulging in antic gestures. But he only wanted milk with his tea. And there is this further parallel between the Little Beings of Africa and the Little People of Ireland. Both are on a curious borderland between the natural and the supernatural. Both are able to ‘propagate procerity’ – I use an elegant phrase of Dr. Johnson’s. This is formally asserted of the Asiki; and in Celtdom we have the legends of the changeling, the little, dark creature found in the cradle of the big, red-haired Celtic baby. And both are material and capable of dealing with material things and of making use of them. Miss Somerville has strange tales of them which are of our own day. Miss Somerville herself had seen the shoe that was found on the lonely hill. It was of the size that a child of about a year old might use, but it was heavily made, in the fashion of a workman’s brogue, and had seen hard wear. And, again, she tells the story of two servants sent on a sudden errand at night. They were driving a car, and at the entrance of a certain town, the harness broke. And there they found a little saddler’s shop, open in the dead of night, and two little men within – described with a shudder as ‘quare’ – to whom the servants told their trouble. They were terrified almost out of their senses; they would not stay in the shop: but the work was done, and done well.

We have here a state of mind which is very hard to understand. What can an Immortal want with a workman’s leather shoe? And how should Beings of another order from that of man, Beings to be beheld with awe and dread of the spirit, undertake saddlery repairs on demand? One would say that the belief that such things are so is impossible; but yet it exists in Ireland, probably to this day; and it is much like the negro belief as to the Asiki.

It is interesting to note, by the way, that Fairyland in Ireland seems strongly associated with leather. There is the matter of the fairy brogue, there is the adventure of the fairy saddlers; and then there is the Leprechaun, who is a fairy cobbler. He is, clearly, a distant cousin of the Asiki. And if, in spite of all his efforts to distract you, you continue to regard him with a fixed gaze, your reward will be a crock of gold.

Arthur Machen, ‘The Little People’ Dreads and Drolls (London 1926)