There cam a strange wight to our town-en’,

And the fient a body did him ken;

He tirled na lang, but he glided ben

Wi’ a dreary, dreary hum.

His face did glare like the glow o’ the west,

When the drumlie cloud has it half o’ercast;

Or the struggling moon when she’s sair distrest.

O sirs! ’twas Aiken-drum.

I trow the bauldest stood aback,

Wi’ a gape and a glower till their lugs did crack,

As the shapeless phantom mum’ling spak –

‘Hae ye wark for Aiken-drum?’

O! had ye seen the bairns’ fright,

As they stared at this wild and unyirthly wight,

As he stauket in ’tween the dark and the light,

And graned out, ‘Aiken-drum!’

‘Sauf us!’ quoth Jock

‘d’ye see sic een;’

Cries Kate, ‘there’s a hole where a nose should hae been;

And the mouth’s like a gash which a horn had ri’en;

Wow! keep’s frae Aiken-drum!’

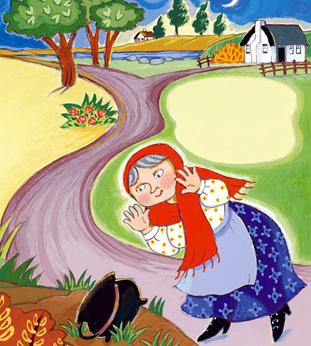

The black dog growling cowered his tail,

The lassie swarfed, loot fa’ the pail;

Rob’s lingle brak as he men’t the flail,

At the sight o’ Aiken-drum.

His matted head on his breast did rest,

A lang blue beard wan’ered down like a vest;

But the glare o’ his e’e nae bard hath exprest,

Nor the skimes o’ Aiken-drum.

Roun’ his hairy form there was naething seen,

But a philabeg o’ the rashes green,

And his knotted knees played ay knoit between:

What a sight was Aiken-drum!

On his wauchie arms three claws did meet,

As they trailed on the grun’ by his taeless feet;

E’en the auld gudeman himsel’ did sweat,

To look at Aiken-drum.

But he drew a score, himsel’ did sain,

The auld wife tried, but her tongue was gane;

While the young ane closer clasped her wean,

And turned frae Aiken-drum.

But the canny auld wife cam till her breath,

And she deemed the Bible might ward aff scaith,

Be it benshee, bogle, ghaist or wraith –

But it fear’t na Aiken-drum.

‘His presence protect us!’ quoth the auld gudeman;

‘What wad ye, where won ye

by sea or by lan’?

I conjure ye — speak — by the Beuk in my han’!’

What a grane ga’e Aiken-drum!

‘I lived in a lan’ where we saw nae sky,

I dwalt in a spot where a burn rins na by;

But I’se dwall now wi’ you, if ye like to try —

Hae ye wark for Aiken-drum?

‘I’ll shiel a’ your sheep i’ the mornin’ sune,

I’ll berry your crap by the light o’ the moon,

And baa the bairns wi’ an unken’d tune,

If ye’ll keep puir Aiken-drum.

‘I’ll loup the linn when ye canna wade,

I’ll kirn the kirn, and I’ll turn the bread;

And the wildest fillie that ever ran rede

I’se tame’t,’ quoth Aiken-drum!

‘To wear the tod frae the flock on the fell —

To gather the dew frae the heather bell —

And to look at my face in your clear crystal well,

Might gie pleasure to Aiken-drum.

‘I’se seek nae guids, gear, bond, nor mark;

I use nae beddin’, shoon, nor sark;

But a cogfu’ o’ brose ’tween the light and dark,

Is the wage o’ Aiken-drum.’

Quoth the wylie auld wife,’The thing speaks weel;

Our workers are scant — we hae routh o’ meal;

Gif he’ll do as he says — be he man, be he de’il,

Wow! we’ll try this Aiken-drum.’

But the wenches skirled ‘he’s no be here!

His eldritch look gars us swarf wi’ fear,

And the fient a ane will the house come near,

If they think but o’ Aiken-drum.

‘For a foul and a stalwart ghaist is he,

Despair sits brooding aboon his e’e bree,

And unchancie to light o’ a maiden’s e’e,

Is the grim glower o’ Aiken-drum.’

‘Puir slipmalabors! Ye hae little wit;

Is’t na hallowmas now, and the crap out yet?’

Sae she silenced them a’ wi’ a stamp o’ her fit;

‘Sit yer wa’s down, Aiken-drum.’

Roun’ a’ that side what wark was dune,

By the streamer’s gleam, or the glance o’the moon;

A word, or a wish — and the Brownie cam sune,

Sae helpfu’ was Aiken-drum.

But he slade aye awa or the sun was up,

He ne’er could look straught on Macmillan’s cup;

They watched — but nane saw him his brose ever sup,

Nor a spune sought Aiken-drum.

On Blednoch banks, and on crystal Cree,

For mony a day a toiled wight was he;

While the bairns played harmless roun’ his knee,

Sae social was Aiken-drum.

But a new-made wife, fu’ o’ rippish freaks,

Fond o’ a’ things feat for the first five weeks,

Laid a mouldy pair o’ her ain man’s breeks

By the brose o’ Aiken-drum.

Let the learned decide, when they convene,

What spell was him and the breeks between;

For frae that day forth he was nae mair seen,

And sair missed was Aiken-drum.

He was heard by a herd gaun by the Thrieve,

Crying ‘Lang, lang now may I greet and grieve;

For alas! I hae gotten baith fee and leave,

O, luckless Aiken-drum!’

Awa! ye wrangling sceptic tribe,

Wi’ your pros and your cons wad ye decide

’Gainst the ’sponsible voice o’

a hale country-side

On the facts ’bout Aiken-drum?

Though the ‘Brownie o’ Blednoch’ lang be gane,

The mark o’ his feet’s left on mony a stane;

And mony a wife and mony a wean

Tell the feats o’ Aiken-drum.

E’en now, light loons that jibe and sneer

At spiritual guests and a’ sic gear,

At the Glashnoch mill hae swat wi’ fear,

And looked roun’ for Aiken-drum.

And guidly folks hae gotten a fright,

When the moon was set, and the stars gied nae light,

At the roaring linn in the howe o’ the night,

Wi’ sughs like Aiken-drum (Nicholson, 1897 76-82).