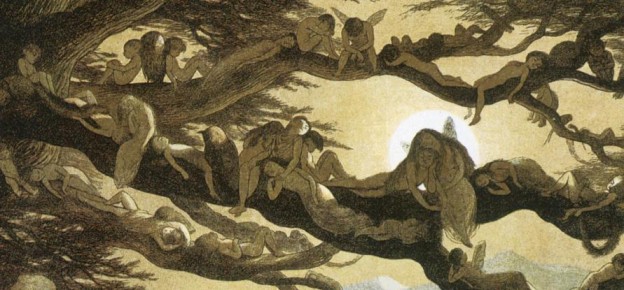

The tale of a woman who was carried off by the fairies is known in practically every district. The woman disappears and, after a lapse of time, sometimes as long as two years, she is seen by her husband in the vicinity of a rath. When asked why she is there, she says the is under a spell and cannot leave her captors. There is, however, one chance of escape. She has discovered that the fairies are moving on a certain night, often the first night of the next full moon, and she will be travelling with them. She knows the route the host will take and asks her husband to wait at a given point and touch her horse with a twig of rowan, which will break the spell. The husband goes to the appointed place but, when he sees the host, he is terrified and drops the rowan. His wife is swept along with the fairies and, later in the night, screams are heard. Next morning blood stains are found in the field. The woman, of course, is never seen again and, it is assumed, that the fairies killed her. (Foster, Ulster 67)