There was once a grown-up lad in the County Leitrim, and he was strong and lively, and the son of a rich farmer. His father had plenty of money, and he did not spare it on the son. Accordingly, when the boy grew up he liked sport better than work, and, as his father had no other children, he loved this one so much that he allowed him to do in everything just as it pleased himself. He was very extravagant, and he used to scatter the gold money as another person would scatter the white. He was seldom to be found at home, but if there was a fair, or a race, or a gathering within ten miles of him, you were dead certain to find him there. And he seldom spent a night in his father’s house, but he used to be always out rambling, and, like Shawn Bwee long ago, there was ‘grádh gach cailin i mbrollach a léine,’ (‘the love of every girl in the breast of his shirt,’) and it’s many’s the kiss he got and he gave, for he was very handsome, and there wasn’t a girl in the country but would fall in love with him, only for him to fasten his two eyes on her, and it was for that someone made this rann on him: ‘Feuch an rógaire ‘g iarraidh póige, Ni h-iongantas mór é a bheith mar atá Ag leanamhaint a gcómhnuidhe d’árnán na gráineóige Anuas ‘s anios ‘s nna chodladh ‘sa’ lá.’ (‘Look at the rogue, it’s for kisses he’s rambling, It isn’t much wonder, for that was his way; He’s like an old hedgehog, at night he’ll be scrambling From this place to that, but he’ll sleep in the day.’)

At last he became very wild and unruly. He wasn’t to be seen day nor night in his father’s house, but always rambling or going on his kailee (night-visit) from place to place and from house to house, so that the old people used to shake their heads and say to one another, ‘it’s easy seen what will happen to the land when the old man dies; his son will run through it in a year, and it won’t stand him that long itself.’

He used to be always gambling and card-playing and drinking, but his father never minded his bad habits, and never punished him. But it happened one day that the old man was told that the son had ruined the character of a girl in the neighbourhood, and he was greatly angry, and he called the son to him, and said to him, quietly and sensibly ‘Avic,’ says he, ‘you know I loved you greatly up to this, and I never stopped you from doing your choice thing whatever it was, and I kept plenty of money with you, and I always hoped to leave you the house and land, and all I had after myself would be gone; but I heard a story of you today that has disgusted me with you. I cannot tell you the grief that I felt when I heard such a thing of you, and I tell you now plainly that unless you marry that girl I’ll leave house and land and everything to my brother’s son. I never could leave it to anyone who would make so bad a use of it as you do yourself, deceiving women and coaxing girls. Settle with yourself now whether you’ll marry that girl and get my land as a fortune with her, or refuse to marry her and give up all that was coming to you; and tell me in the morning which of the two things you have chosen.’

‘Och! Domnoo Sheery! father, you wouldn’t say that to me, and I such a good son as I am. Who told you I wouldn’t marry the girl?’ says he.

But his father was gone, and the lad knew well enough that he would keep his word too; and he was greatly troubled in his mind, for as quiet and as kind as the father was, he never went back of a word that he had once said, and there wasn’t another man in the country who was harder to bend than he was.

The boy did not know rightly what to do. He was in love with the girl indeed, and he hoped to marry her sometime or other, but he would much sooner have remained another while as he was, and follow on at his old tricks, drinking, sporting, and playing cards; and, along with that, he was angry that his father should order him to marry, and should threaten him if he did not do it.

‘Isn’t my father a great fool,’ says he to himself. ‘I was ready enough, and only too anxious, to marry Mary; and now since he threatened me, faith I’ve a great mind to let it go another while.’

His mind was so much excited that he remained between two notions as to what he should do. He walked out into the night at last to cool his heated blood, and went on to the road. He lit a pipe, and as the night was fine he walked and walked on, until the quick pace made him begin to forget his trouble. The night was bright, and the moon half full. There was not a breath of wind blowing, and the air was calm and mild. He walked on for nearly three hours, when he suddenly remembered that it was late in the night, and time for him to turn. ‘Musha! I think I forgot myself,’ says he, ‘it must be near twelve o’clock now.’

The word was hardly out of his mouth, when he heard the sound of many voices, and the trampling of feet on the road before him. ‘I don’t know who can be out so late at night as this, and on such a lonely road,’ said he to himself. He stood listening, and he heard the voices of many people talking through other, but he could not understand what they were saying. ‘Oh, wirra!’ (‘Oh Mary!’) says he, ‘I’m afraid. It’s not Irish or English they have; it can’t be they’re Frenchmen!’ He went on a couple of yards further, and he saw well enough by the light of the moon a band of little people coming towards him, and they were carrying something big and heavy with them. ‘Oh, murder!’ says he to himself, ‘sure it can’t be that they’re the good people that’s in it!’ Every rib (single hair) of hair that was on his head stood up, and there fell a shaking on his bones, for he saw that they were coming to him fast.

He looked at them again, and perceived that there were about twenty little men in it, and there was not a man at all of them higher than about three feet or three feet and a half, and some of them were grey, and seemed very old. He looked again, but he could not make out what was the heavy thing they were carrying until they came up to him, and then they all stood round about him. They threw the heavy thing down on the road, and he saw on the spot that it was a dead body.

He became as cold as the Death, and there was not a drop of blood running in his veins when an old little grey maneen came up to him and said, ‘Isn’t it lucky we met you, Teig O’Kane?’

Poor Teig could not bring out a word at all, nor open his lips, if he were to get the world for it, and so he gave no answer.

‘Teig O’Kane,’ said the little grey man again, ‘isn’t it timely you met us?’

Teig could not answer him.

‘Teig O’Kane,’ says he, ‘the third time, isn’t it lucky and timely that we met you?’

But Teig remained silent, for he was afraid to return an answer, and his tongue was as if it was tied to the roof of his mouth.

The little grey man turned to his companions, and there was joy in his bright little eye. ‘And now,’ says he, ‘Teig O’Kane hasn’t a word, we can do with him what we please. Teig, Teig,’ says he, ‘you’re living a bad life, and we can make a slave of you now, and you cannot withstand us, for there’s no use in trying to go against us. Lift that corpse.’

Teig was so frightened that he was only able to utter the two words, ‘I won’t’, for as frightened as he was, he was obstinate and stiff, the same as ever.

‘Teig O’Kane won’t lift the corpse,’ said the little maneen, with a wicked little laugh, for all the world like the breaking of a lock of dry kippeens (bundle of twigs), and with a little harsh voice like the striking of a cracked bell. ‘Teig O’Kane won’t lift the corpse, make him lift it’, and before the word was out of his mouth they had all gathered round poor Teig, and they all talking and laughing through other.

Teig tried to run from them, but they followed him, and a man of them stretched out his foot before him as he ran, so that Teig was thrown in a heap on the road. Then before he could rise up the fairies caught him, some by the hands and some by the feet, and they held him tight, in a way that he could not stir, with his face against the ground. Six or seven of them raised the body then, and pulled it over to him, and left it down on his back. The breast of the corpse was squeezed against Teig’s back and shoulders, and the arms of the corpse were thrown around Teig’s neck. Then they stood back from him a couple of yards, and let him get up. He rose, foaming at the mouth and cursing, and he shook himself, thinking to throw the corpse off his back. But his fear and his wonder were great when he found that the two arms had a tight hold round his own neck, and that the two legs were squeezing his hips firmly, and that, however strongly he tried, he could not throw it off, any more than a horse can throw off its saddle. He was terribly frightened then, and he thought he was lost. ‘Ochone! for ever’, said he to himself, ‘it’s the bad life I’m leading that has given the good people this power over me. I promise to God and Mary, Peter and Paul, Patrick and Bridget, that I’ll mend my ways for as long as I have to live, if I come clear out of this danger, and I’ll marry the girl.’

The little grey man came up to him again, and said he to him, ‘Now, Teigeen,’ says he, ‘you didn’t lift the body when I told you to lift it, and see how you were made to lift it; perhaps when I tell you to bury it you won’t bury it until you’re made to bury it!’

‘Anything at all that I can do for your honour,’ said Teig, ‘I’ll do it,’ for he was getting sense already, and if it had not been for the great fear that was on him, he never would have let that civil word slip out of his mouth.

The little man laughed a sort of laugh again. ‘You’re getting quiet now, Teig,’ says he. ‘I’ll go bail but you’ll be quiet enough before I’m done with you. Listen to me now, Teig O’Kane, and if you don’t obey me in all I’m telling you to do, you’ll repent it. You must carry with you this corpse that is on your back to Teampoll-Démus, and you must bring it into the church with you, and make a grave for it in the very middle of the church, and you must raise up the flags and put them down again the very same way, and you must carry the clay out of the church and leave the place as it was when you came, so that no one could know that there had been anything changed. But that’s not all. Maybe that the body won’t be allowed to be buried in that church; perhaps some other man has the bed, and, if so, it’s likely he won’t share it with this one. If you don’t get leave to bury it in Teampoll-Démus, you must carry it to Carrick-fhad-vic-Orus, and bury it in the churchyard there; and if you don’t get it into that place, take it with you to Teampoll-Ronan; and if that churchyard is closed on you, take it to Imlogue-Fada; and if you’re not able to bury it there, you’ve no more to do than to take it to Kill-Breedya, and you can bury it there without hindrance. I cannot tell you what one of those churches is the one where you will have leave to bury that corpse under the clay, but I know that it will be allowed you to bury him at some church or other of them. If you do this work rightly, we will be thankful to you, and you will have no cause to grieve; but if you are slow or lazy, believe me we shall take satisfaction of you.’

When the grey little man had done speaking, his comrades laughed and clapped their hands together. ‘Glic! Glic! Hwee! Hwee!’ they all cried, ‘go on, go on, you have eight hours before you till daybreak, and if you haven’t this man buried before the sun rises, you’re lost.’ They struck a fist and a foot behind on him, and drove him on in the road. He was obliged to walk, and to walk fast, for they gave him no rest.

He thought himself that there was not a wet path, or a dirty boreen (lane), or a crooked contrary road in the whole county that he had not walked that night. The night was at times very dark, and whenever there would come a cloud across the moon he could see nothing, and then he used often to fall. Sometimes he was hurt, and sometimes he escaped, but he was obliged always to rise on the moment and to hurry on. Sometimes the moon would break out clearly, and then he would look behind him and see the little people following at his back. And he heard them speaking amongst themselves, talking and crying out, and screaming like a flock of sea-gulls; and if he was to save his soul he never understood as much as one word of what they were saying.

He did not know how far he had walked, when at last one of them cried out to him, ‘Stop here!’ He stood, and they all gathered round him.

‘Do you see those withered trees over there?’ says the old boy to him again. ‘Teampoll-Démus is among those trees, and you must go in there by yourself, for we cannot follow you or go with you. We must remain here. Go on boldly.’

Teig looked from him, and he saw a high wall that was in places half broken down, and an old grey church on the inside of the wall, and about a dozen withered old trees scattered here and there round it. There was neither leaf nor twig on any of them, but their bare crooked branches were stretched out like the arms of an angry man when he threatens. He had no help for it, but was obliged to go forward. He was a couple of hundred yards from the church, but he walked on, and never looked behind him until he came to the gate of the churchyard. The old gate was thrown down, and he had no difficulty in entering. He turned then to see if any of the little people were following him, but there came a cloud over the moon, and the night became so dark that he could see nothing. He went into the churchyard, and he walked up the old grassy pathway leading to the church. When he reached the door, he found it locked. The door was large and strong, and he did not know what to do. At last he drew out his knife with difficulty, and stuck it in the wood to try if it were not rotten, but it was not.

‘Now,’ said he to himself, ‘I have no more to do; the door is shut, and I can’t open it.’

Before the words were rightly shaped in his own mind, a voice in his ear said to him, ‘Search for the key on the top of the door, or on the wall.’

He started. ‘Who is that speaking to me?’ he cried, turning round; but he saw no one. The voice said in his ear again, ‘Search for the key on the top of the door, or on the wall.’

‘What’s that?’ said he, and the sweat running from his forehead, ‘who spoke to me?’

‘It’s I, the corpse, that spoke to you!’ said the voice.

‘Can you talk?’ said Teig.

‘Now and again,’ said the corpse.

Teig searched for the key, and he found it on the top of the wall. He was too much frightened to say any more, but he opened the door wide, and as quickly as he could, and he went in, with the corpse on his back. It was as dark as pitch inside, and poor Teig began to shake and tremble.

‘Light the candle,’ said the corpse.

Teig put his hand in his pocket, as well as he was able, and drew out a flint and steel. He struck a spark out of it, and lit a burnt rag he had in his pocket. He blew it until it made a flame, and he looked round him. The church was very ancient, and part of the wall was broken down. The windows were blown in or cracked, and the timber of the seats was rotten. There were six or seven old iron candlesticks left there still, and in one of these candlesticks Teig found the stump of an old candle, and he lit it. He was still looking round him on the strange and horrid place in which he found himself, when the cold corpse whispered in his ear, ‘Bury me now, bury me now; there is a spade and turn the ground.’ Teig looked from him, and he saw a spade lying beside the altar. He took it up, and he placed the blade under a flag that was in the middle of the aisle, and leaning all his weight on the handle of the spade, he raised it. When the first flag was raised it was not hard to raise the others near it, and he moved three or four of them out of their places. The clay that was under them was soft and easy to dig, but he had not thrown up more than three or four shovelfuls, when he felt the iron touch something soft like flesh. He threw up three or four more shovelfuls from around it, and then he saw that it was another body that was buried in the same place.

‘I am afraid I’ll never be allowed to bury the two bodies in the same hole,’ said Teig, in his own mind. ‘You corpse, there on my back,’ says he, ‘will you be satisfied if I bury you down here?’ But the corpse never answered him a word.

‘That’s a good sign,’ said Teig to himself. ‘Maybe he’s getting quiet,’ and he thrust the spade down in the earth again. Perhaps he hurt the flesh of the other body, for the dead man that was buried there stood up in the grave, and shouted an awful shout. ‘Hoo! hoo!! hoo!!! Go! go!! go!!! Or you’re a dead, dead, dead man!’ And then he fell back in the grave again. Teig said afterwards, that of all the wonderful things he saw that night, that was the most awful to him. His hair stood upright on his head like the bristles of a pig, the cold sweat ran off his face, and then came a tremor over all his bones, until he thought that he must fall.

But after a while he became bolder, when he saw that the second corpse remained lying quietly there, and he threw in the clay on it again, and he smoothed it overhead and he laid down the flags carefully as they had been before. ‘It can’t be that he’ll rise up any more,’ said he.

He went down the aisle a little further, and drew near to the door, and began raising the flags again, looking for another bed for the corpse on his back. He took up three or four flags and put them aside, and then he dug the clay. He was not long digging until he laid bare an old woman without a thread upon her but her shirt. She was more lively than the first corpse, for he had scarcely taken any of the clay away from about her, when she sat up and began to cry, ‘Ho, you bodach (clown)! Ha, you bodach! Where has he been that he got no bed?’

Poor Teig drew back, and when she found that she was getting no answer, she closed her eyes gently, lost her vigour, and fell back quietly and slowly under the clay. Teig did to her as he had done to the man—he threw the clay back on her, and left the flags down overhead.

He began digging again near the door, but before he had thrown up more than a couple of shovelfuls, he noticed a man’s hand laid bare by the spade. ‘By my soul, I’ll go no further, then,’ said he to himself; ‘what use is it for me?’ And he threw the clay in again on it, and settled the flags as they had been before.

He left the church then, and his heart was heavy enough, but he shut the door and locked it, and left the key where he found it. He sat down on a tombstone that was near the door, and began thinking. He was in great doubt what he should do. He laid his face between his two hands, and cried for grief and fatigue, since he was dead certain at this time that he never would come home alive. He made another attempt to loosen the hands of the corpse that were squeezed round his neck, but they were as tight as if they were clamped; and the more he tried to loosen them, the tighter they squeezed him. He was going to sit down once more, when the cold, horrid lips of the dead man said to him, ‘Carrick-fhad-vic-Orus,’ and he remembered the command of the good people to bring the corpse with him to that place if he should be unable to bury it where he had been.

He rose up, and looked about him. ‘I don’t know the way,’ he said.

As soon as he had uttered the word, the corpse stretched out suddenly its left hand that had been tightened round his neck, and kept it pointing out, showing him the road he ought to follow. Teig went in the direction that the fingers were stretched, and passed out of the churchyard. He found himself on an old rutty, stony road, and he stood still again, not knowing where to turn. The corpse stretched out its bony hand a second time, and pointed out to him another road, not the road by which he had come when approaching the old church. Teig followed that road, and whenever he came to a path or road meeting it, the corpse always stretched out its hand and pointed with its fingers, showing him the way he was to take.

Many was the cross-road he turned down, and many was the crooked boreen he walked, until he saw from him an old burying-ground at last, beside the road, but there was neither church nor chapel nor any other building in it. The corpse squeezed him tightly, and he stood. ‘Bury me, bury me in the burying-ground,’ said the voice.

Teig drew over towards the old burying-place, and he was not more than about twenty yards from it, when, raising his eyes, he saw hundreds and hundreds of ghosts – men, women, and children – sitting on the top of the wall round about, or standing on the inside of it, or running backwards and forwards, and pointing at him, while he could see their mouths opening and shutting as if they were speaking, though he heard no word, nor any sound amongst them at all.

He was afraid to go forward, so he stood where he was, and the moment he stood, all the ghosts became quiet, and ceased moving. Then Teig understood that it was trying to keep him from going in, that they were. He walked a couple of yards forwards, and immediately the whole crowd rushed together towards the spot to which he was moving, and they stood so thickly together that it seemed to him that he never could break through them, even though he had a mind to try. But he had no mind to try it. He went back broken and dispirited, and when he had gone a couple of hundred yards from the burying-ground, he stood again, for he did not know what way he was to go. He heard the voice of the corpse in his ear, saying ‘Teampoll-Ronan’, and the skinny hand was stretched out again, pointing him out the road.

As tired as he was, he had to walk, and the road was neither short nor even. The night was darker than ever, and it was difficult to make his way. Many was the toss he got, and many a bruise they left on his body. At last he saw Teampoll-Ronan from him in the distance, standing in the middle of the burying-ground. He moved over towards it, and thought he was all right and safe, when he saw no ghosts nor anything else on the wall, and he thought he would never be hindered now from leaving his load off him at last. He moved over to the gate, but as he was passing in, he tripped on the threshold. Before he could recover himself, something that he could not see seized him by the neck, by the hands, and by the feet, and bruised him, and shook him, and choked him, until he was nearly dead; and at last he was lifted up, and carried more than a hundred yards from that place, and then thrown down in an old dyke, with the corpse still clinging to him.

He rose up, bruised and sore, but feared to go near the place again, for he had seen nothing the time he was thrown down and carried away.

‘You corpse, up on my back,’ said he, ‘shall I go over again to the churchyard?’ But the corpse never answered him. ‘That’s a sign you don’t wish me to try it again,’ said Teig.

He was now in great doubt as to what he ought to do, when the corpse spoke in his ear, and said ‘Imlogue-Fada’.

‘Oh, murder!’ said Teig, ‘must I bring you there? If you keep me long walking like this, I tell you I’ll fall under you.’

He went on, however, in the direction the corpse pointed out to him. He could not have told, himself, how long he had been going, when the dead man behind suddenly squeezed him, and said, ‘There!’

Teig looked from him, and he saw a little low wall, that was so broken down in places that it was no wall at all. It was in a great wide field, in from the road; and only for three or four great stones at the corners, that were more like rocks than stones, there was nothing to show that there was either graveyard or burying-ground there.

‘Is this Imlogue-Fada? Shall I bury you here?’ said Teig.

‘Yes,’ said the voice.

‘But I see no grave or gravestone, only this pile of stones,’ said Teig.

The corpse did not answer, but stretched out its long fleshless hand, to show Teig the direction in which he was to go. Teig went on accordingly, but he was greatly terrified, for he remembered what had happened to him at the last place. He went on, ‘with his heart in his mouth,’ as he said himself afterwards; but when he came to within fifteen or twenty yards of the little low square wall, there broke out a flash of lightning, bright yellow and red, with blue streaks in it, and went round about the wall in one course, and it swept by as fast as the swallow in the clouds, and the longer Teig remained looking at it the faster it went, till at last it became like a bright ring of flame round the old graveyard, which no one could pass without being burnt by it. Teig never saw, from the time he was born, and never saw afterwards, so wonderful or so splendid a sight as that was. Round went the flame, white and yellow and blue sparks leaping out from it as it went, and although at first it had been no more than a thin, narrow line, it increased slowly until it was at last a great broad band, and it was continually getting broader and higher, and throwing out more brilliant sparks, till there was never a colour on the ridge of the earth that was not to be seen in that fire; and lightning never shone and flame never flamed that was so shining and so bright as that.

Teig was amazed; he was half dead with fatigue, and he had no courage left to approach the wall. There fell a mist over his eyes, and there came a soorawn (vertigo) in his head, and he was obliged to sit down upon a great stone to recover himself. He could see nothing but the light, and he could hear nothing but the whirr of it as it shot round the paddock faster than a flash of lightning.

As he sat there on the stone, the voice whispered once more in his ear, ‘Kill-Breedya’ and the dead man squeezed him so tightly that he cried out. He rose again, sick, tired, and trembling, and went forwards as he was directed. The wind was cold, and the road was bad, and the load upon his back was heavy, and the night was dark, and he himself was nearly worn out, and if he had had very much farther to go he must have fallen dead under his burden.

At last the corpse stretched out its hand, and said to him, ‘Bury me there’.

‘This is the last burying-place’, said Teig in his own mind; ‘and the little grey man said I’d be allowed to bury him in some of them, so it must be this; it can’t be but they’ll let him in here.’

The first faint streak of the ring of day was appearing in the east, and the clouds were beginning to catch fire, but it was darker than ever, for the moon was set, and there were no stars.

‘Make haste, make haste!’ said the corpse; and Teig hurried forward as well as he could to the graveyard, which was a little place on a bare hill, with only a few graves in it. He walked boldly in through the open gate, and nothing touched him, nor did he either hear or see anything. He came to the middle of the ground, and then stood up and looked round him for a spade or shovel to make a grave. As he was turning round and searching, he suddenly perceived what startled him greatly, a newly-dug grave right before him. He moved over to it, and looked down, and there at the bottom he saw a black coffin. He clambered down into the hole and lifted the lid, and found that (as he thought it would be) the coffin was empty. He had hardly mounted up out of the hole, and was standing on the brink, when the corpse, which had clung to him for more than eight hours, suddenly relaxed its hold of his neck, and loosened its shins from round his hips, and sank down with a plop into the open coffin.

Teig fell down on his two knees at the brink of the grave, and gave thanks to God. He made no delay then, but pressed down the coffin lid in its place, and threw in the clay over it with his two hands; and when the grave was filled up, he stamped and leaped on it with his feet, until it was firm and hard, and then he left the place.

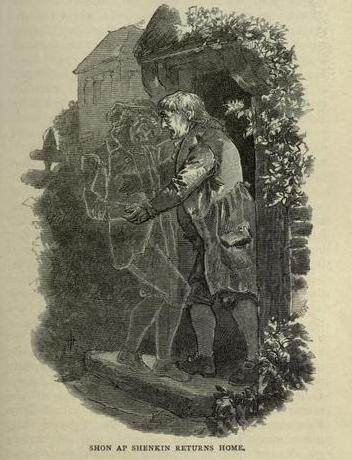

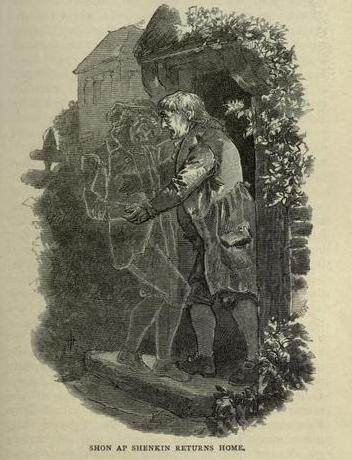

The sun was fast rising as he finished his work, and the first thing he did was to return to the road, and look out for a house to rest himself in. He found an inn at last, and lay down upon a bed there, and slept till night. Then he rose up and ate a little, and fell asleep again till morning. When he awoke in the morning he hired a horse and rode home. He was more than twenty-six miles from home where he was, and he had come all that way with the dead body on his back in one night.

All the people at his own home thought that he must have left the country, and they rejoiced greatly when they saw him come back. Everyone began asking him where he had been, but he would not tell anyone except his father.

He was a changed man from that day. He never drank too much; he never lost his money over cards; and especially he would not take the world and be out late by himself of a dark night.

He was not a fortnight at home until he married Mary, the girl he had been in love with; and it’s at their wedding the sport was, and it’s he was the happy man from that day forward, and it’s all I wish that we may be as happy as he was.

Yeats, Irish Fairy and Folk Tales, 16-33 [Douglas Hyde translated from Gaelic original]